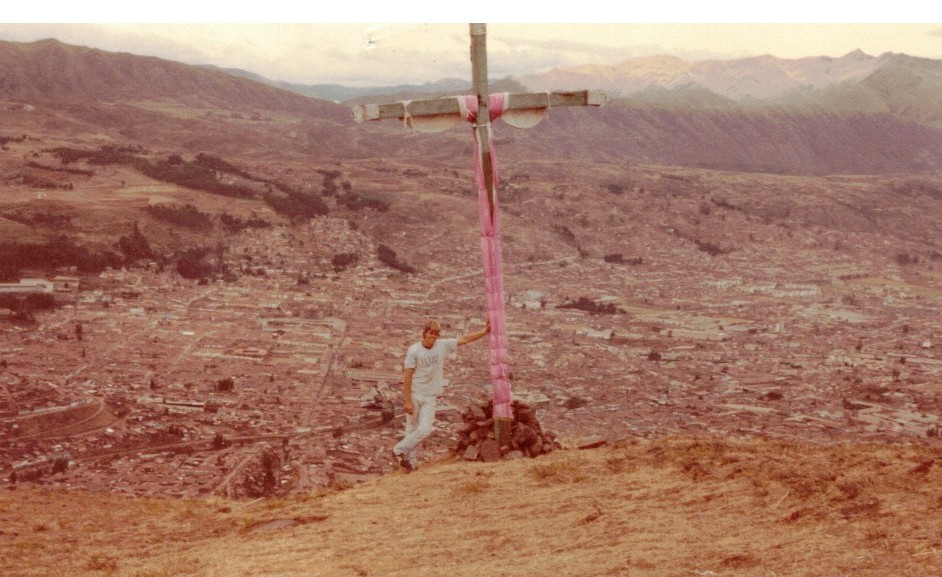

In October of 1982, I climbed dirt roads on the outskirts of Cusco, Perú with a college classmate. Cusco, in a bowled valley 11,152 feet above sea level in the beating heart of the Andes Mountain range, shrank behind us as we ascended. In front of us, unending stacks of mountain tops beckoned. The whole experience—the expanse and sheer beauty of the Andes, the history of the ancient Incan capital, the freedom to hike where few of our contemporaries even imagined—was exhilarating. The two of us vowed to return some day to Perú.

Augustana College (Rock Island, Illinois) had what was called a “foreign quarter study” program. With some forty other classmates and four professors, we spent ten weeks in Mexico, Colombia and Perú. Our history teacher on the trip, Dr. Tom Brown, mesmerized us with lectures on the Black and White Legends of the Spanish Conquest. Toward the end of the trip, a handful of us talked about spinning Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer” as the first thing we’d do upon returning home. He came dancing across the water, with his galleons and guns . . .

Participating in the program changed my life. I did go back to Perú, as a seminary student, and learned Spanish de verdad. Subsequently, I’ve spent three plus decades working as a pastor in Texas, using English, of course, y el bendito Español. Often times I’ve described myself as “a missionary to white people.” That description isn’t necessarily pejorative. Another way to describe the work I’ve done and continue to do: I’m a “bridger.”

Yale history professor Greg Grandin’s new book, America, América, tells a broader story of American history—of English-speaking, Spanish-speaking and Portuguese-speaking America. In Grandin’s telling of the American story, there is no dichotomy of US and Latin American histories as North, Central and South American histories bridge together.

I sense that Grandin would consider himself a “bridger” as well. His ability to merge Latin American events within the larger framework of “American history” works. His occasional use of Spanish in the text is well-placed and adds appropriate spice and effect.

The shared evil of slavery is the initial touchpoint of his telling.

Whereas the United States needed the brutal Civil War to resolve its adherence to slavery, the majority of Latin American nations—Cuba and Brazil are the outliers, not abolishing slavery, respectively, until 1886 and 1888—wrote abolitionism into their founding constitutions in the early nineteenth century. Independence from Spain logically translated into freedom for all inhabitants—whether brown, black or white; male or female; native- or foreign-born.

The Spanish priest Bartolomé de Las Casas (1484–1566) exposed the wickedness and inhumanity of Spanish colonial slavery. Early on in the Conquest, Las Casas himself was an encomienda owner with slaves. His eventual, steady conversion to abolitionism, primarily documented in his A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies (written in 1542 and published in 1552), established a tradition that abolitionists built upon for close to 300 years, cresting with the leadership of the “Great Liberator,” Simón Bolívar.

Liberty for all was an American concept established—on constitutional paper, at least—by a dozen newly established Latin American countries by 1825, while at the same time the number of slaves in the United States grew to more than 2 million. It would be another 40 years until slavery was officially abolished in the US.

On December 1, 1936, President Franklin Roosevelt arrived in Buenos Aires, Argentina to give the keynote address at the Inter-American Conference for the Maintenance of Peace. Grandin recounts how FDR championed his “good neighbor policy” as a guard against the possibility of European fascism—ascendant in Germany and Italy, and rising in Spain—establishing itself in the Americas. Additionally, the “good neighbor policy” was Roosevelt’s promise of no armed US intervention into the twenty-one Latin American countries represented at the conference. Roosevelt’s formula—social welfare, freedom of thought, free commerce, and mutual defense—echoing some of his New Deal constructs, offered, he said, “hope for peace and a more abundant life” for Latin Americans and the whole world.

In this pre-WW II era, German and Italian nationals lived in established communities in Argentina, Paraguay, Uruguay, Chile and Perú. The threat of fascist advance in South America was real.

Two Roosevelt administrators, Henry Wallace and Sumner Welles, worked the “good neighbor policy” in Latin America. Wallace, the Secretary of Agriculture (and Roosevelt’s vice-president from 1941–44), was convinced that raising the world’s standard of living was the surest way to promote democracy in the midst of fascist advances. He promoted labor clauses favoring worker rights—fair wages, health care, and a ban on prisoner labor—in government procurement contracts. Welles, a bilingual State Department envoy who specialized in Latin American affairs, was of the opinion that a peaceful and secure world was only possible if the gap between “the haves” and “the have nots” was narrowed.

Their naysayers were legion and vociferous. By the time Roosevelt died (in office) in 1945, Wallace’s and Welles’s influence had waned. Even so, their viewpoints stand out as high-water marks of New Deal thinking. Poverty and inequality breed discontent and unrest, much more so in the modern world than in times previous.

As the Cold War and the thwarting of communism took on absolute precedence in US foreign policy, the good neighbor policy toward Latin America disappeared like a mouse scurrying into hole. The era of US support of proxy wars in Central and South American countries commenced—first in Guatemala, later in Nicaragua and El Salvador. The US would later carry out covert operations in Honduras, Panama and Haiti.

Grandin details how the International Court of Justice—the legal arm of the United Nations—ruled in 1986 that the US was guilty of waging an illegal war in Nicaragua and imposed a $17 billion reparations judgment on the US. The court ruled that Washington’s patronage of the Contras was illegal as was the mining Nicaragua’s harbors and distributing “how-to” torture manuals to anti-Sandinistas. In response, the Reagan administration simply announced it was withdrawing from the court’s jurisdiction. Grandin calls it a watershed moment of unilateralism and the blunting of international law.

Shortly thereafter, with the fall of the Soviet Union and the absence of anything akin to FDR’s good neighbor policy, US and Latin American relations took on, according to Grandin, the status of “informal dependency.” The economic policies of neoliberalism, or globalization—as it has done in the US—has redistributed wealth upward in Latin American countries as its populaces have suffered through economic austerity measures, lower wages, hollowed-out social services and weakened labor protections. Inequality is on the rise in Latin America. As wealth siphons upward, so does political power.

The authoritarian right—Trump in the US, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Milei in Argentina, Bukele in El Salvador—and the accompanying reemergence of fascism will be the topic of my next blog on Grandin’s America, América.

This is the first of two blog posts on the new book, America, América: A New History of the New World (Penguin Press, 2025) by Yale historian Greg Grandin.

T. Carlos “Tim” Anderson – I’m a Protestant minister and Director of Austin City Lutherans (ACL), an organization of partners in Austin, Texas working together to serve low-income individuals and families.